I know I owe my readers an uplifting and helpful look at something in their photographic lives, and I also know that I may be starting to sound like a broken record when I warn about the perils of threats to the truths of our lives like “fake news” and, quite recently, AI, or Artificial Intelligence.

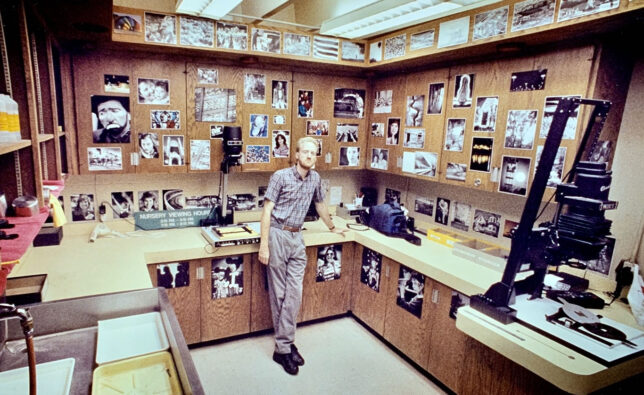

In the photographic press just this week is an article from a reliable source indicating there have been 15.47 billion images created by AI as of August 2023, and presently there are about 34 million new AI images being created each day.

The most obvious solution is to simply unplug. But there certainly is a lot more to it. Even if you unplug yourself, get a library card and start borrowing books, millions of people around us are still ingesting artificial content, and, among other things, they vote, and they vote with their dollars.

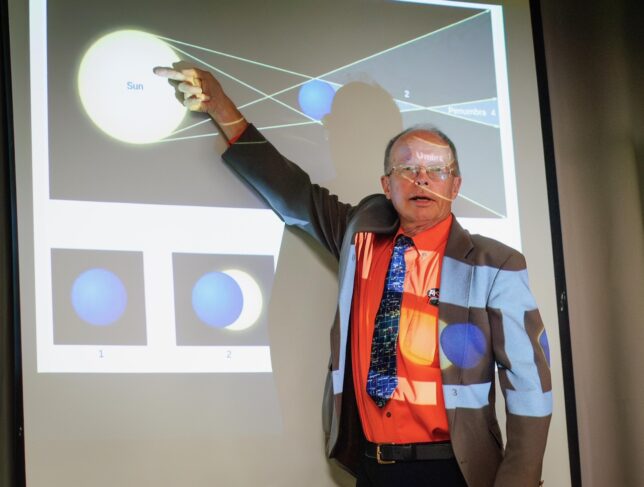

At this point, AI is still relatively easy to spot and call out, at least for us among the visually literate. But compared to just 18-months ago, when AI was cranking out people with 11 fingers on each hand and four-foot-tall hair, AI is improving by leaps and bounds.

The next question that troubles me isn’t that AI can fool us, but why would it want to? I get that entities that want to make money will have no problem making money with AI, but the issue goes deeper. Will humanity actually go dow this road, in which every photograph they see is a fake? What would be the over-arching consequence of this? Will it be “The Matrix” mixed with “1984”?

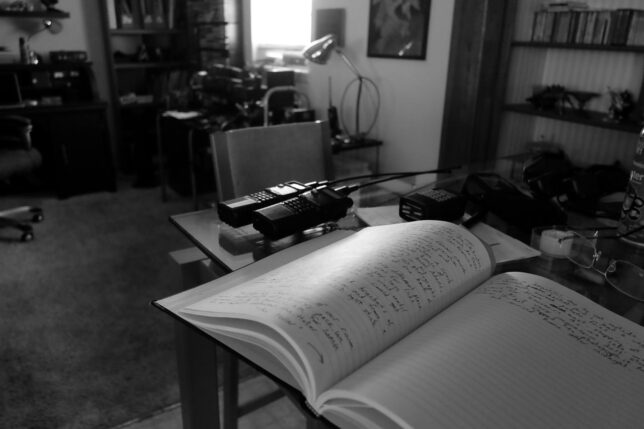

And finally, I am feeling very nostalgic for the “golden age” of the Internet, when it was new, fun, and held so much promise. Even without AI, the internet is so much less interesting and inviting than it was at the end of the 1990s. Don’t believe me? Do a web search for something you really like, then count how many results – probably page after page – are not information about that thing, but entities selling it to you.